Escaping the Guest: How Custom LLM Workflows Uncovered Critical VMSVGA Vulnerabilities

- Novel LLM Methodology: Cyera Research Labs developed a custom workflow that enables LLMs to trace complex code logic paths and identify critical vulnerabilities that traditional tools miss.

- AI as a Reasoning Engine: The approach uses LLMs to actively reason about code behavior and exploitability, not just pattern match—a fundamental shift in automated vulnerability research.

- Proven Results: The methodology independently discovered CVE-2025-53024 in VirtualBox's VMSVGA driver, demonstrating it can find expert-level vulnerabilities systematically and at scale.

Background

Cyera Research Labs is advancing the use of Large Language Models (LLMs) in vulnerability research. In this study, our researchers fine-tuned existing LLMs to create specialized workflows that move beyond static analysis to perform contextual code tracing. This approach allowed us to independently uncover a critical Guest-to-Host escape vulnerability in VirtualBox’s VMSVGA driver.

While traditional tools failed to detect the bug - and off-the-shelf LLMs lacked the specific context - our LLM-driven protocol successfully identified the deep logic flaw, enabling us to develop a Proof of Concept (PoC) that crashed the hypervisor. This work is part of Cyera Research Labs’ broader mission to explore the intersection of AI and security, demonstrating how LLMs can serve as force multipliers in deep technical analysis.

Vulnerability research is traditionally a high-latency process. It requires deep understanding of complex codebases, manual tracing of data flows, and significant time spent validating leads. The “10x Researcher” isn’t someone who types faster; it’s someone who can filter noise faster.

In this research, we explored whether AI agents-specifically LLMs operating with custom personas and protocols-could accelerate this process to find critical Guest-to-Host escape vulnerabilities in Oracle VirtualBox.

This experiment targeted the VirtualBox VBox/Devices directory, specifically the SVGA graphics adapter. The results were significant:

- Automated failure: Standard static analysis tools like Semgrep failed to identify critical logic bugs.

- AI success: A custom AI agent workflow identified a critical Integer Overflow in

vmsvgaR3RectCopy. - Validation: We successfully exploited this vulnerability to achieve a write-primitive on the host.

- Collision: We independently discovered and reported this vulnerability. Oracle confirmed it as valid but informed us it had already been reported by ZDI, assigning it CVE-2025-53024.

This post details the methodology, the false starts, and the technical deep dive into the vulnerability found.

Drowning in Noise: Why Semgrep & Basic LLMs Failed

Before deploying our custom agents, we followed a standard, rigorous vulnerability research methodology: automated static analysis followed by AI-assisted triage. The goal was to quickly filter low-hanging fruit before diving into manual review.

The Semgrep Dragnet

We started by scanning the entire src/VBox/Devices/Graphics directory using Semgrep with the comprehensive semgrep-rules/c ruleset. We cast a wide net, looking for anything related to memory management, integer arithmetic, and buffer handling.

The output turned into an enormous, noisy dataset—over four million characters long. It included thousands of “findings,” but the signal-to-noise ratio was terrible. Semgrep flagged:

- Every usage of

memcpythat depended on a variable size (even if validated 5 lines up). - Generic “integer overflow potential” warnings on almost every arithmetic operation.

- Style-based warnings about unsafe functions that are standard in driver development.

The “AI Triage” Attempt (Claude 4.1 Opus)

Faced with thousands of leads, manually reviewing each one was unfeasible. We decided to use a powerful LLM to act as a “Tier 1 Analyst” to filter the noise.

We utilized Claude 4.1 Opus to process the Semgrep JSON output. The prompt instructed the model to:

- Read the Semgrep finding.

- Check Reachability: Determine if the flagged code was accessible from Guest-controlled vectors (I/O ports, VRAM, MMIO).

- Validate: Check if sanitization logic existed in the surrounding code.

- Classify: Mark findings as “unreachable,” “sanitized,” or “vulnerable.”

The Failure of Context-Free Triage

Despite the sophisticated prompt, this workflow failed to uncover any critical bugs. We churned through hundreds of findings, only to end up with a folder full of irrelevant lead files:

Why did it fail?

- Missing Context: The AI was analyzing individual code snippets provided by Semgrep or looking at functions in isolation. It couldn’t see the state of the device. For example, it would flag a missing check in a helper function, not realizing that the caller (three layers up the stack) had already sanitized the input.

- False Confidence: The model was excellent at explaining why a specific Semgrep rule matched, but poor at judging exploitability. It frequently hallucinated that “input validation is missing” because it couldn’t see the validation logic in the header files or the main command dispatcher.

- The “Linter” Trap: By feeding the AI Semgrep output, we biased it to think like a Linter. It focused on syntax patterns (like “using

strcpyis bad”) rather than logic patterns (like “this integer wrap-around bypasses the bounds check”).

This failure was a crucial pivot point. We realized that treating the AI as a “filter” for static analysis tools was inefficient. To find deep logic bugs, the AI needed to be the hunter, not just the cleaner. This led us to the “Prompt Strategy” in Phase 2.

A New Protocol: Turning the LLM into a Tracer

To overcome these limitations, we pivoted our approach based on emerging research on LLMs for vulnerability analysis. We moved away from simple “bug finding” queries and instead engineered a specific research protocol grounded in recent academic findings.

The Science of Code Flow Tracing

Recent studies have demonstrated that LLMs excel at tracing data flow through complex code structures, often outperforming traditional static analysis in handling semantic nuance.

LLMDFA: Analyzing Dataflow in Code with Large Language Models (arXiv:2402.10754) demonstrates that LLMs can effectively model data dependencies without the need for compilation, a critical capability when analyzing partial driver code.

CRUXEval: A Benchmark for Code Reasoning, Understanding and Execution (arXiv:2401.03065) highlights the ability of models like Claude to predict execution output and input-output mappings, which is essential for tracing Guest-controlled inputs to Host sinks.

We hypothesized that by explicitly instructing the model to "trace" the execution path rather than "find bugs," we could leverage this latent capability to map the attack surface more accurately. This hypothesis was grounded in empirical evidence: the foundational studies above demonstrate that LLMs possess inherent code-tracing capabilities that can be effectively applied to security analysis. With this capability validated, the question shifted from "Can LLMs trace execution paths?" to "How do we direct this capability toward domain-specific vulnerability patterns?"

Context Loading (“Fine-Tuning” via Prompting)

A key insight from Automated Vulnerability Validation and Verification (arXiv:2509.24037) and Teams of LLM Agents can Exploit Zero-Day Vulnerabilities (arXiv:2406.01637) is that generic models struggle with domain-specific vulnerability classes unless primed with relevant definitions and examples.

Instead of performing expensive parameter fine-tuning, we implemented “Context Fine-Tuning” via the system prompt. We augmented the model’s context with:

- CWE Definitions: Specific criteria for Integer Overflows (CWE-190), Use-After-Free (CWE-416), and Race Conditions (CWE-362), Stack Based Overflow (CWE-121), Heap Based Overflow.

- Attack Vectors: Examples of Guest-to-Host attack surfaces (MMIO, PIO, VRAM, Hypercalls).

- Negative Constraints: Explicit instructions on what not to flag (style issues, unreachable code).

- Vulnerabilities Examples: Explicit examples of relevant vulnerabilities and their analysis code dependant

This strategy effectively transformed Claude from a general-purpose model into a specialized Guest-to-Host security auditor-primed to recognize virtualization-specific attack patterns without expensive retraining. The papers above validated that such prompt-based specialization can achieve domain-specific vulnerability detection comparable to fine-tuned models.

The Resulting Protocol

Combining the flow-tracing capabilities with the vulnerability-specific context, we created a rigorous analysis protocol. We stopped asking the AI to “find bugs” and instead instructed it to act as a specialized AI Security Auditing Agent.

The protocol forced the agent to follow a strict analysis flow for every file:

- Check Reachability: Determine whether the vulnerable code path is reachable from guest-controlled attack surface, especially via Device I/O (MMIO/PIO), Guest -> Host hypercalls, or Guest-controlled buffers (DMA, shared memory, VRAM). If the issue cannot be reached from a guest VM, mark it as

"unreachable": true.

- Check for Memory Safety Issues: Focus on finding specific CWEs based on the provided definitions:

- Integer overflows / underflows (CWE-190)

- Stack/Heap buffer overflows (CWE-121/122)

- Use-After-Free (CWE-416)

- Race conditions (CWE-362)

- Recheck the Flow for Exploitability: Rewalk the entire flow from guest input → vulnerable sink. Confirm whether checks (bounds, locking, sanitization) are missing, weak, or bypassable.

This shift was decisive. It moved the AI from being a “Linter” (pattern matching) to being a “Tracer” (reasoning about execution state), directly enabling the discovery of the complex logic bugs in the subsequent phases.

General LLM Vulnerability Research Note (The “Depth” Problem)

While this protocol was successful, it is important to acknowledge a fundamental limitation identified in FormulaOne: Measuring the Depth of Algorithmic Reasoning Beyond Competitive Programming (arXiv:2507.13337). The study highlights that current LLMs struggle significantly with “expertise problems”- tasks requiring deep, multi-step reasoning that goes beyond surface-level pattern matching.

Real-world vulnerability research is an expertise domain. A complex exploit chain might require 15, 20, or even 30 logical steps to go from a primitive to a stable shell. Current models operate effectively at a “depth” of 2-3 steps (e.g., spotting a missing check). They often fail to maintain the coherent state tracking required for deep 20-step chains (e.g., “If I corrupt this pointer here, how does it affect the heap layout three function calls later?”).

To truly reach state-of-the-art performance in vulnerability research, we believe the next frontier is not just better prompting, but a different type of learning paradigm-one that trains models to operate at the “right depth” of reasoning (20-30 steps) rather than just predicting the next token. We plan to explore this “Deep Reasoning for Exploitation” in a future blog post.

The Perfect False Positive: A Lesson in Global Context

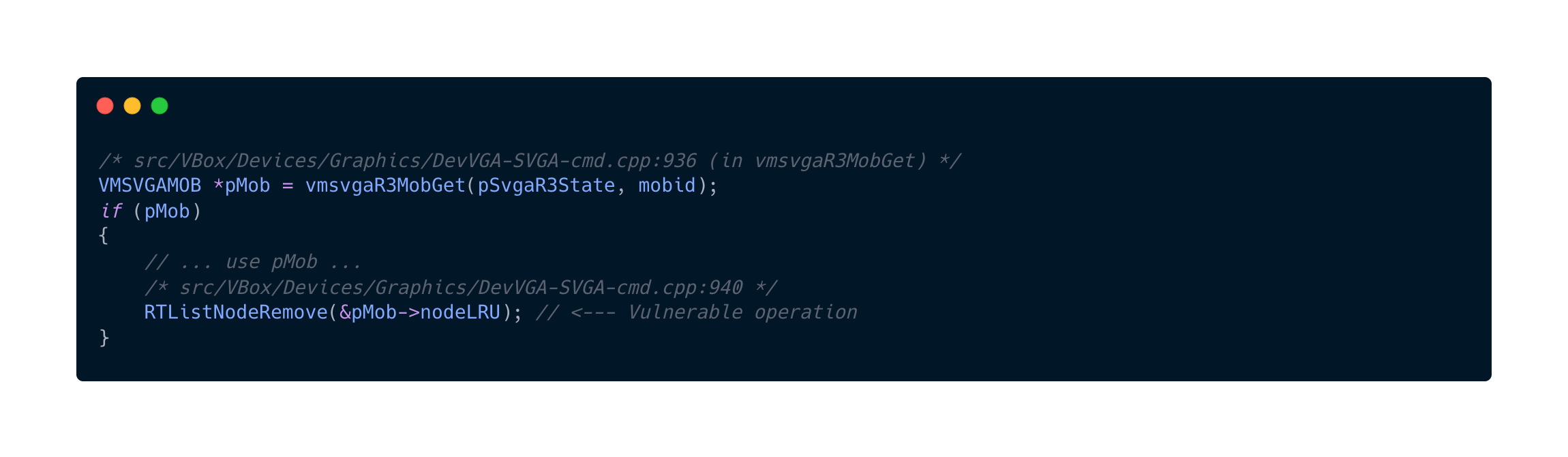

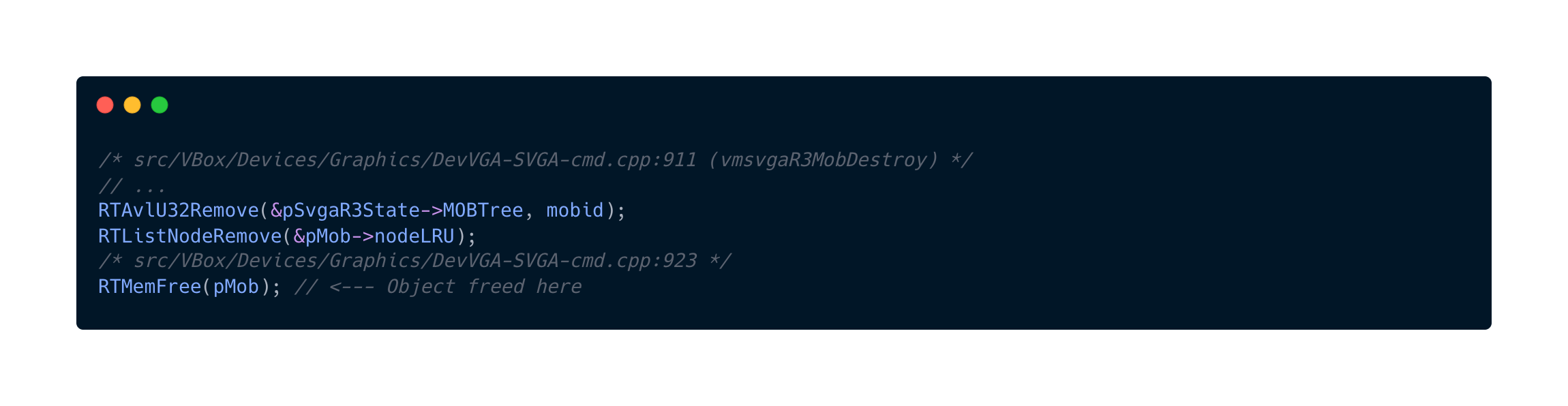

The first major lead generated by the agent was a Use-After-Free (UAF) vulnerability in src/VBox/Devices/Graphics/DevVGA-SVGA-cmd.cpp.

The agent flagged a race condition in the Memory Object Buffer (MOB) management. The logic appeared sound and followed a classic UAF pattern.

The Vulnerable Pattern

The agent identified two competing operations reachable from the Guest

1. Thread A (Usage):

2. Thread B (Destruction):

If Thread B executes RTMemFree while Thread A has already passed the pMob check but hasn’t yet called RTListNodeRemove, Thread A will attempt to unlink a node inside freed memory. This is a textbook write-what-where primitive (modifying prev->next and next->prev pointers in freed memory).

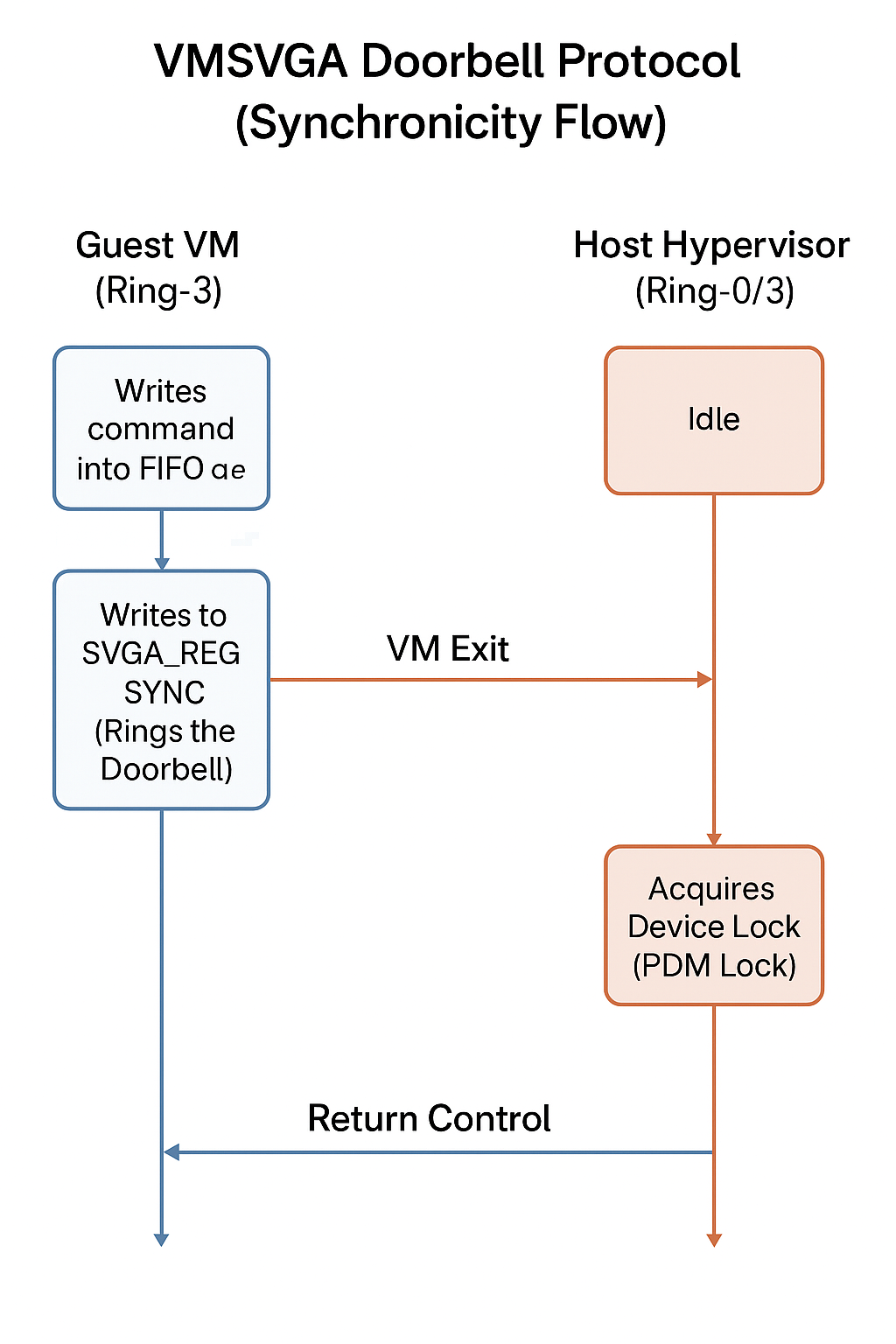

The Discovery of Synchronicity (“Ring the Bell”)

We initially attempted to trigger this with aggressive multi-threaded racing, but failed. We then provided the AI with broader context-specifically the device communication protocols defined in the headers and the communicate.c test POC logic.

The AI performed a deeper analysis of the command submission mechanism and discovered the “Doorbell Protocol”, which enforces synchronization:

1. FIFO Queue (Guest Side): The Guest writes 3D commands (like DEFINE_GB_MOB or UPDATE_GB_SURFACE) into a shared memory ring buffer (FIFO). These writes are just memory operations and do not immediately trigger Host processing.

2. The “Doorbell” (Guest Side): To notify the Host that new commands are ready, the Guest performs an I/O port write to SVGA_REG_SYNC (Value 1).

3. TVM Exit (Hypervisor): This I/O write is a privileged operation that triggers a VM Exit. The CPU pauses the Guest execution and transfers control to the VirtualBox Hypervisor.

4. The Main Thread Lock (Host Side): The Hypervisor handles the I/O exit by acquiring the device lock (VirtualBox's PDM device lock, analogous to QEMU's BQL).

5. Serialized Execution: The DevVGA-SVGA.cpp dispatcher reads the FIFO and executes all pending commands in a tight loop, sequentially, within that single thread context. It does not release the lock until the batch is processed.

The Reality Check (Why the UAF Died)

This “Doorbell Protocol” effectively serializes the “concurrent” Guest operations. Even if the Guest OS has two threads running on two vCPUs-one sending “Usage” commands and one sending “Destruction” commands-they ultimately funnel into the same FIFO.

The race condition requires vmsvgaR3MobDestroy to execute during the execution of vmsvgaR3MobGet. But because of the single-threaded dispatcher:

- Scenario A: The “Usage” command is first in the FIFO. It runs to completion (retrieves MOB, uses it). Then the “Destruction” command runs. Safe.

- Scenario B: The “Destruction” command is first. It runs to completion (destroys MOB). Then the “Usage” command runs. It calls

vmsvgaR3MobGet, which returns NULL because the MOB is gone. Safe.

There is no preemption point inside the command handlers. The “Race” was an illusion created by looking at the code without understanding the runtime execution model.

Why Did AI Miss This Initially?

The initial failure to detect this serialization highlights a key weakness in LLM-based auditing: Local vs. Global Context.

- Local Vision: When looking at

DevVGA-SVGA-cmd.cpp, the AI saw two functions manipulating a shared object without locks. It correctly identified a “Thread Safety Violation” pattern. - Global Blindness: It did not initially “know” that these functions are only ever called from a single-threaded dispatcher located in a different file (

DevVGA-SVGA.cpp) or that the I/O port handler enforces a global lock.

It was only after we explicitly fed it the communication protocol documentation and the communicate.c POC that it could link the high-level architecture to the low-level code flaw. This reinforces the need for RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation) systems that can provide architectural context to code analysis agents.

The Needle in the Haystack: vmsvgaR3RectCopy

The agent’s second major lead was a mathematical anomaly in the vmsvgaR3RectCopy function.

Understanding vmsvgaR3RectCopy

This function implements the SVGA_CMD_RECT_COPY command, a fundamental 2D acceleration primitive. Its purpose is to move rectangular blocks of pixels within the VRAM buffer (Video RAM). This is commonly used for:

- Scrolling: Moving the entire screen content up or down when the user scrolls a webpage.

- Window Movement: Dragging a window across the desktop requires copying its pixel data from the old coordinates to the new ones.

- Back-buffering: Copying a rendered frame from an off-screen buffer to the visible screen area.

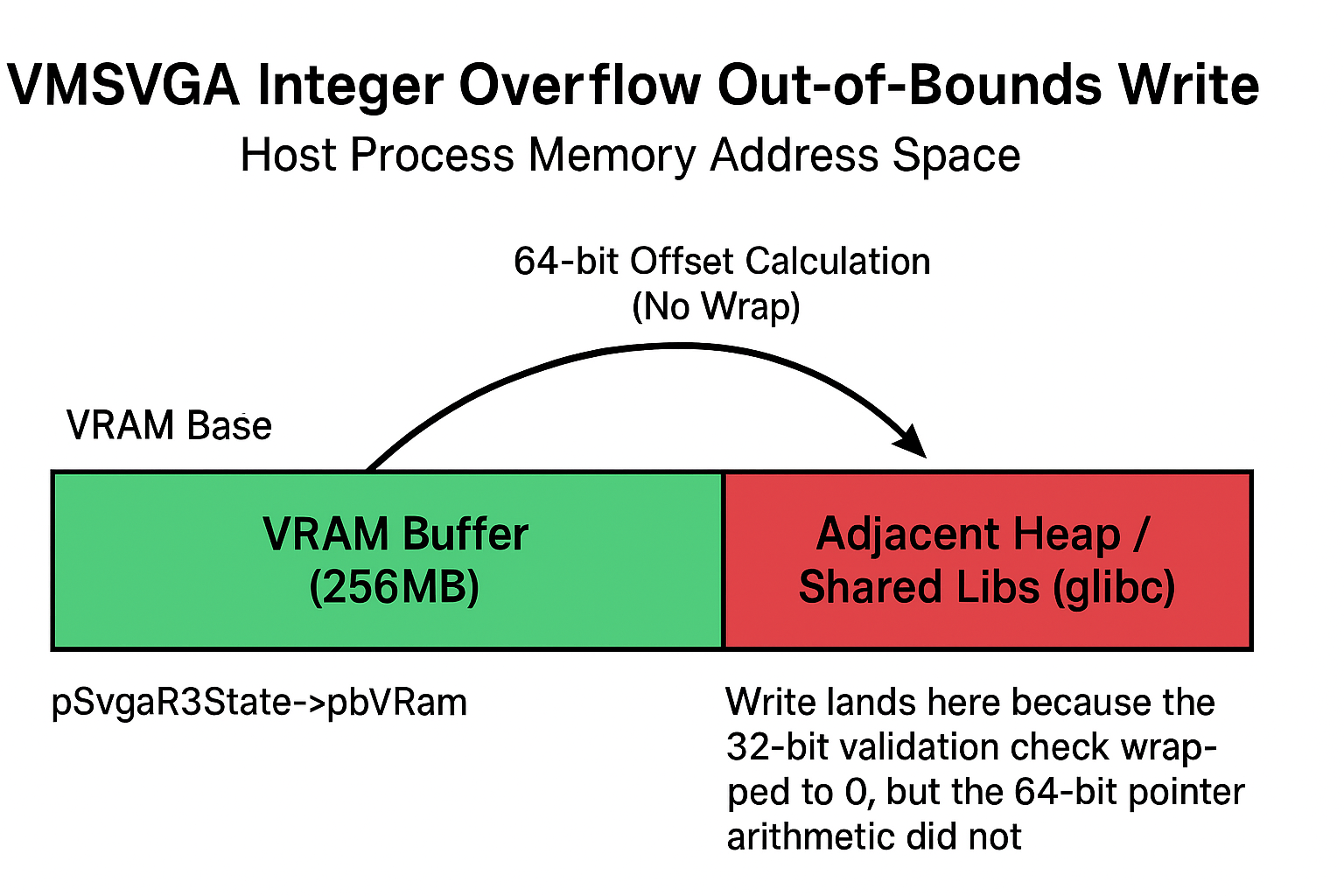

Crucially, this function operates entirely in the Host’s address space but uses relative offsets provided by the Guest. It calculates a source address (pSrc) and a destination address (pDst) by adding Guest-provided X/Y coordinates to the base address of the VRAM allocation (pSvgaR3State->pbVRam). Because VRAM is just a linear chunk of heap memory on the Host, any copy operation that exceeds the bounds of this buffer risks reading or writing to adjacent Host memory-a classic Out-of-Bounds (OOB) access.

The Vulnerable Code

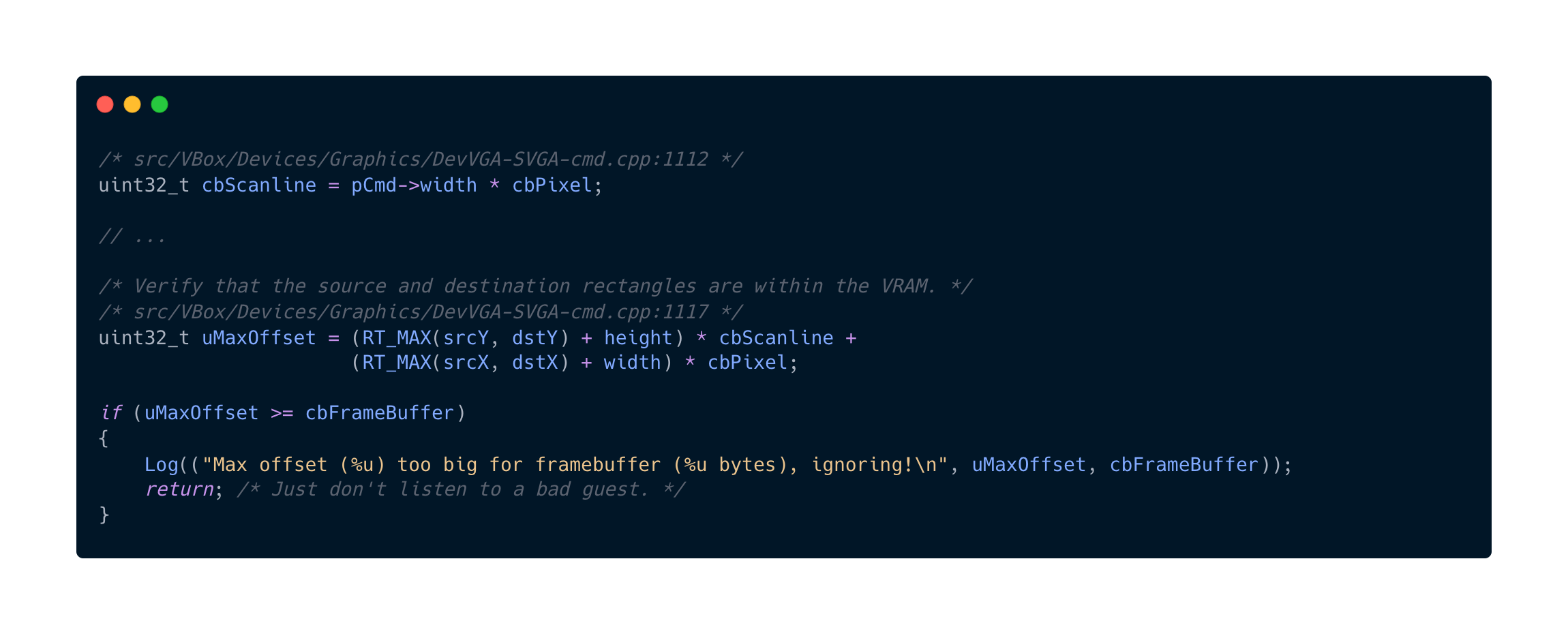

The vulnerable code block was intended to validate that the copy operation stays within the bounds of the Framebuffer (VRAM).

The Analysis

The agent identified a critical mismatch:

uMaxOffsetuint32_t(32-bit unsigned integer).cbScanlineis derived from Guest input (pCmd->width) and can be large.dstYandheightare Guest-controlled 32-bit integers.

The Validation Logic Failure

The validation logic calculates the “end” of the rectangle. If a malicious guest provides values such that the multiplication overflows the 32-bit limit, the result uMaxOffset will wrap around to a small value.

The Math of the Exploit:

- Target: Bypass the check

uMaxOffset >= cbFrameBuffer. - Constraint:

cbFrameBufferis typically 256MB (0x10000000). - Input Values:

dstY=8191(0x1FFF)height=1cbScanline=1,048,576(0x100000- 1MB)cbPixel=4

Let’s calculate uMaxOffset:

In hex, 8,589,934,592 is 0x200000000. This value is too large for a 32-bit integer (uint32_t). It wraps modulo 2^32: 0x200000000 % 0x100000000 = 0.

So, uMaxOffset becomes 0 (plus the small X-offset part). 0 < 256MB. The check passes.

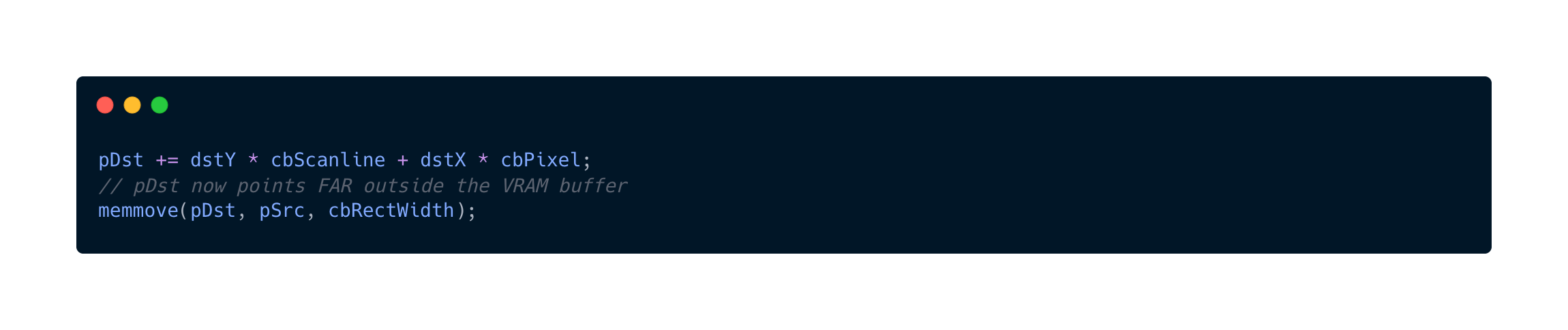

The Consequence

The driver assumes the coordinates are valid. It then proceeds to perform a memmove using the original inputs (which are relative offsets).

Crucially, while the validation variable uMaxOffset was explicitly typed as uint32_t (causing the wrap-around check to pass), the actual pointer arithmetic for pDst on the 64-bit Host promotes to size_t. This means the offset addition does not wrap, pointing pDst to a valid address far outside the VRAM buffer. In the VirtualBox process, the VRAM is often allocated via mmap, and directly adjacent to it are other heap allocations or loaded shared libraries.

From Math to Primitive: Building the Exploit

This Integer Overflow provided two powerful primitives:

- Out-of-Bounds Read (Info Leak): By manipulating the source coordinates (

srcY) to overflow, we could force the emulator to copy data from Host memory (outside VRAM) into the Guest’s VRAM.- Exploit: Guest reads the VRAM content to extract sensitive Host process memory (heap addresses, vtable pointers, libc base address).

- Impact: Defeats ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization).

- Out-of-Bounds Write (Code Execution): By manipulating the destination coordinates (

dstY), we could copy data from the Guest’s VRAM into arbitrary Host memory.- Exploit: Guest fills VRAM with shellcode or ROP chains, then triggers the overflow to copy it over a function pointer (e.g., in a C++ vtable).

- Impact: Arbitrary Code Execution (ACE) on the Host.

Accelerating the POC with AI

Finding the bug is only half the battle. The second, often more time-consuming half is building a stable test POC to trigger it. This is where the AI agent proved to be a transformative force multiplier.

Traditionally, testing a graphics driver vulnerability requires writing a custom kernel module or a complex user-space driver to map MMIO regions, initialize the FIFO, and craft raw commands. This “setup tax” can take days of engineering before you even test your first hypothesis.

The AI Advantage:

- Instant Boilerplate: We fed the AI the C++ header files (

DevVGA-SVGA.h), and it auto-generated the corresponding C structs and bitwise macros for our PoC. - “Time to First Crash”: Instead of spending 3 days fighting with I/O permission bitmaps and

mmaplogic, the agent generated a working user-space POC (communicate.c) using/dev/memin under 30 minutes. - Iterative Refinement: When we needed to test the “Ring the Bell” theory, we simply asked the agent to “update the POC to write to the SYNC register after every command.” It refactored the entire command submission loop instantly.

This capability drastically reduced the feedback loop. We could test a hypothesis (“Does this register trigger a VM exit?”), fail, tweak the code, and retry in minutes rather than hours. The AI didn’t just find the needle; it built the magnet we used to pull it out.

Defeating the Fortress: Bypassing ASLR & NX

Before weaponizing our primitives, we had to map the defensive landscape.

The “Triple Architecture” Setup

Our testing environment mimicked a rigorous, layered virtualization setup:

- Host: Windows 11 Physical Machine.

- Level 1 Guest: Ubuntu 22.04.5 Desktop (running inside VirtualBox). This served as our “victim” Hypervisor host.

- Level 2 Guest: Ubuntu Server 22.04.5 (running inside the nested VirtualBox). This was our “attacker” machine.

This “Triple Emulation” setup was crucial. It allowed us to debug the Level 1 Hypervisor (the victim) from the outside (Host Windows) while launching attacks from the inside (Level 2 Guest), simulating a real-world cloud breakout scenario.

System-Level Mitigations (Ubuntu 22.04)

The victim system (Ubuntu 22.04) enforces strict default protections:

- ASLR (Address Space Layout Randomization): With

randomize_va_space=2, the base addresses of the heap, stack, and shared libraries are randomized on every execution. This prevents us from hardcoding any addresses in our exploit. - Glibc Heap Hardening: Modern

mallocimplementations include “Safe Linking,” which XORs linked list pointers with random cookies. This effectively kills trivial heap metadata corruption attacks.

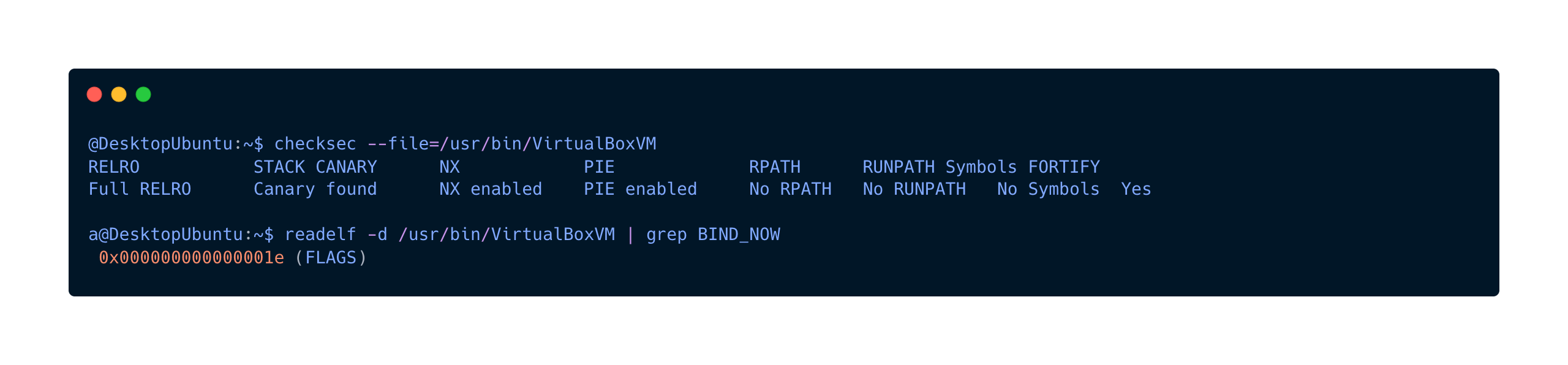

Binary Mitigations (VirtualBoxVM)

Analyzing the VirtualBoxVM binary revealed a hardened target. We verified this using standard tools:

- Full RELRO: The Global Offset Table (GOT) is Read-Only. We cannot simply overwrite

printfwithsystem. - NX (No-Execute): The heap is non-executable. We cannot place shellcode in VRAM and jump to it. We are forced to use Code Reuse attacks (ROP).

- PIE (Position Independent Executable): The binary itself is loaded at a random address. We don’t know where the internal functions are.

The Bypass Strategy

Given these defenses, we needed a strategy to bypass ASLR and NX. We decided to chain our two primitives:

- Info Leak (Read Primitive): Use the Out-of-Bounds Read (triggered by overflowing

srcY) to scan the Host memory adjacent to VRAM. Our goal is to find a pointer intolibc.so. Sincelibcis often mapped near VRAM, we can leak a valid address to defeat ASLR and calculate the base oflibc. - VTable Hijacking (Write Primitive): Once we have the

libcbase, we target a specific Virtual Method Table (VTable) withinlibc’swritable data segment (e.g.,_IO_file_jumpsor similar structures used during file operations or error handling). By overwriting a function pointer in this table with the address ofsystemor a ROP gadget, we can gain code execution.

The Target – LibC VTable

To bypass PIE, we targeted libc.so instead of the VirtualBoxVM binary. Why?

- The VRAM allocation is often adjacent to other mmap allocations, including shared libraries.

libcstructures (like_IO_FILEvtables) are well-known targets.- By overwriting a function pointer within a

libcstructure managed on the heap, we could redirect execution to a “magic gadget” (system("/bin/sh")) once we resolved the ASLR slide via the info leak.

Execution: The Full Chain

To validate the finding, we developed rect_copy_test.c and svga_write_primitive_crash_poc.c.

The Demo Exploit Chain

1. Initialization: The PoC initializes the SVGA device and maps the FIFO command queue.

2. Setup VRAM: We define a screen with a massive pitch (1MB) to facilitate the overflow multiplication.

3. Heap Spray (Payload): We fill the VRAM with a recognizable pattern (0xBADC0FFE). c /

4. Trigger: We send a SVGA_CMD_RECT_COPY command with the calculated overflow parameters.

Full Execution Chain (From Leak to Shell)

While the demo crashes the host, the weaponized exploit follows a precise sequence:

- Grooming: We repeatedly define large screens to align the VRAM buffer adjacent to the

libc.somapping in the Host’s virtual address space. - The Leak (Step 1): We trigger the

vmsvgaR3RectCopyoverflow with a modifiedsrcYto perform an Out-of-Bounds Read. This isn’t a single shot; we execute this in a loop. We iteratively increment the offset to scan 4KB chunks of Host memory adjacent to our VRAM, effectively “walking” the heap. - Analysis: In each iteration, the Guest reads the VRAM content (which now contains Host data) and scans for known

libcsignatures (pointers to_IO_2_1_stderr_or similar symbols). We repeat the read/scan loop until a valid signature is found. Once found, we calculate the exact base address oflibcand the ASLR slide. - The Overwrite (Step 2): We recalculate the

dstYoverflow parameters to target the_IO_file_jumpsvtable (or a similar function pointer array) inside the writable data segment of the now-locatedlibc. - Payload: We use the Write Primitive to replace the

__overflowor__xsputnfunction pointer with the address ofsystem(). - Trigger: We force

libcto use the corrupted structure (e.g., by triggering an error log on the Host), causing it to jump tosystem("/bin/sh")instead of printing an error message.

Impact Analysis

When the PoC runs in the Guest VM:

- The VirtualBox Host process receives the command.

vmsvgaR3RectCopycalculates the bounds. The 32-bit integer wraps to 0. validation passes.memmoveis called. The destination pointer is calculated relative to the VRAM base:VRAM_BASE + (0x1000 * 0x100000).- This offset (

0x10000000= 256MB) is exactly the size of the VRAM. The write lands immediately after the VRAM buffer. - This adjacent memory typically contains metadata for the memory allocator or other device structures.

- CRASH: The Host process crashes immediately due to heap corruption or accessing unmapped pages.

In our video artifact (VBoxGuestToHostWritePrimitiveCrash.mp4), the execution of the PoC leads to an immediate “Guru Meditation” or full process crash of the VirtualBox GUI, confirming the write primitive. Debugging the core dump showed our 0xBADC0FFE pattern present in the registers and memory at the crash site.

Conclusion: The Augmented Researcher

We compiled our findings into a detailed technical advisory, which we submitted to Oracle.

The response confirmed the validity of the vulnerability. It was identified as a duplicate of an issue reported shortly before our submission (assigned CVE-2025-53024) and was patched in VirtualBox 7.2.0_RC1. The patch introduced size64_t (64-bit integers) for the bounds calculation, preventing the wrap-around.

The Verdict: Are we “10x Researchers”?

The AI-augmented workflow did not replace the researcher. It failed to understand threading contexts (the UAF rabbit hole) and required human validation to confirm the exploitability of the overflow.

However, it significantly optimized the process:

- Noise Filter: It completely ignored the hundreds of “style” warnings that Semgrep produced.

- Logic Hunter: It identified a subtle arithmetic bug-validating

(A+B)*Cthat is notoriously difficult for humans to spot during a quick skim, especially when variable types are implicit. - Exploit Assistant: It correctly reasoned about the math required to bypass the check, saving us hours of “guess and check.”

This research demonstrates that while AI cannot run on “autopilot,” a customized, persona-driven AI agent acts as a powerful force multiplier. It doesn’t just “find bugs”; it generates high-quality hypotheses that a skilled researcher can then verify and weaponize.

.svg)